Racial inequities found in Delaware’s regional transportation network

A Wilmington Area Planning Council report found black and Latino populations have been historically disadvantaged by the region’s transportation network.

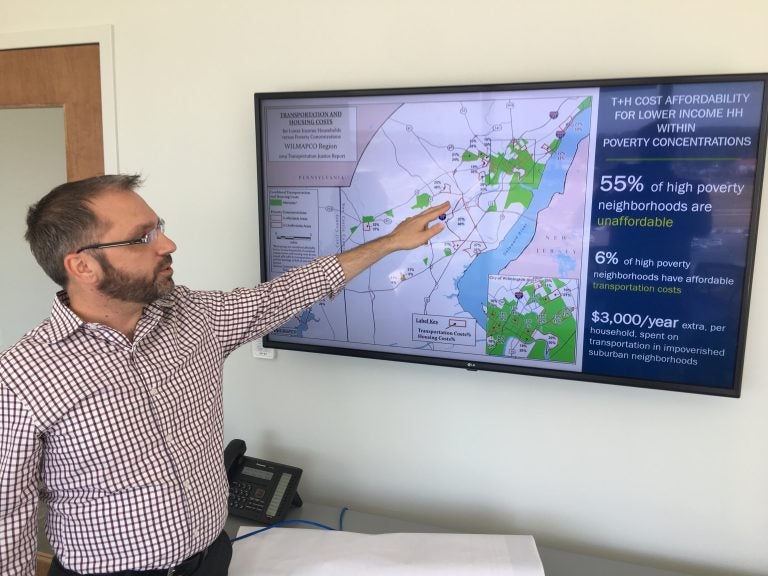

WILMAPCO’s Bill Swiatek points to a map from the group’s Transportation Justice Plan that shows the high cost of transportation and housing for those living in high poverty areas. (Mark Eichmann/WHYY)

As part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Wilmington Area Planning Council is required to ensure that its operations and planning are done in a way that is nondiscriminatory. The group makes long-range plans for transportation infrastructure in New Castle County, Delaware, and neighboring Cecil County, Maryland.

But WILMAPCO’s Transportation Justice Plan has found that blacks, Latinos, and low-income residents have more difficulty traveling where they need to go. Those groups also experience higher rates of bike and pedestrian crashes.

Fifty-four percent of those commuting to work by transit were black, even though blacks make up 21% of the region’s population. “Since about twice as much time is needed to reach work via transit versus a car trip, chronic public-transit inefficiency is an equity concern,” the report said.

Though some of that inequality has been built up as a result of decades of development, more recent numbers show a lack of equality in transportation spending, according to WILMAPCO principal planner Bill Swiatek.

“One of the things we found was that black neighborhoods got about 38% less spending between 2002 and 2018 on what we would call community-based transportation projects,” Swiatek said. “That was a key finding, and something we need to start correcting.”

In addition to collecting data from the U.S. Census Bureau, WILMAPCO surveyed 600 residents on their access to activities such as grocery shopping, medical care, and family and social events.

The report found that 47% of those living in households earning less than $25,000 per year were kept from doing their normal activities by a lack of available transportation. Only 9% of the region’s highest-earning households reported the same.

Traffic volume was 39% higher in black neighborhoods than in predominantly white areas. Pedestrian crashes were 29% higher in black neighborhoods, and bicycle crashes were 20% higher.

“We think that kind of ties back to the fact that … many of our black neighborhoods were within the city of Wilmington and you have a lot more people walking around there; you also have a lot of car traffic, and so there were a lot of folks getting hit there,” Swiatek said.

Impoverished communities also saw heavier traffic volumes that were 39% above the average.

“The roads are not designed in such a way to make it easy for your travel to and from your destination,” said Kenyetta McCurdy Byrd, chief operating officer of REACH Riverside at the Kingswood Community Center in Wilmington. The city’s Riverside community sits along heavily traveled Northeast Boulevard. She said community residents without cars are sometimes forced to walk long distances in the busy streets.

“The sidewalks are not wide enough, they’re not usually handicap-accessible,” McCurdy Byrd said. “If you don’t have a sidewalk on which to walk, you’re forced to walk in the street.”

That could contribute to higher incidents of pedestrian and bicycle crashes in areas like Riverside. It’s difficult for those residents to travel on foot to get to the nearest grocery store, which is about a mile and a half away, making Riverside what is considered a food desert.

“Neighborhoods that have fewer resources tend to have inadequate or no bike lanes, [no] wide sidewalks on which to walk,” McCurdy Byrd said. “You see the difference in physical structures from one neighborhood to the next.”

The inequities in the system won’t be easily corrected, but Swiatek said the Transportation Justice Plan is a way to focus future planning on fixing the problems.

“It took decades to create this issue, and hopefully it doesn’t take that long to start correcting it, but definitely this report shines light on some of the inequities that we have,” he said. “We’ve already started some conversations with how we can begin to have those corrected.”

The Transportation Justice Plan recommends prioritizing road projects in black and low-income areas to start fixing the problems. The group also recommends improvements to fixed-route bus performance and travel time from impoverished and black neighborhoods to employment centers.

McCurdy Byrd applauded WILMAPCO’s plans to better engage the black community and those who live in low-income areas.

“Many are not aware of who they are. It was only through my professional career that I was introduced to who they were. As a resident, I didn’t even know that they existed,” she said. “Community engagement is definitely the way to go.”

Next month, the plan is expected to be approved by the full WILMAPCO Council, which includes leaders from both the Maryland and Delaware Departments of Transportation. The group will also work to do more outreach to black, Latino, and low-income residents, who the study showed were much less familiar with the planning council’s work than whites and higher-income earners.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.