Philly says it’s simple: Narcan saves lives. Knowing when to use it can be more complicated

Philadelphia wants residents to carry Narcan to prevent overdose deaths. But in the face of a possible emergency, a reporter found the reality is harder than it seems.

Listen 6:12

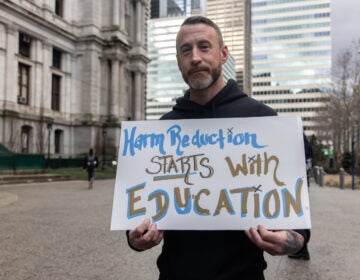

Jasmine Johnson (right), offers Narcan to people using drugs in McPherson Square Park in Kensington. The man refused her offer because he maintained the woman was breathing, and did not want to risk sending her into withdrawal. (Erika Schroeder/WHYY)

On a 90-degree afternoon in July, in the shade of a tree next to the library in Kensington’s McPherson Square Park, I watched a couple sit down, and matter-of-factly prepare syringes, and inject heroin. The man injected in his arm, the woman in her neck.

The city of Philadelphia has tried to clean up the square — known as “Needle Park” — and ramped up the police presence. There was even a group of kids playing on a nearby Slip ‘N Slide that day. But this is still a scene that plays out everyday in this spot and the surrounding neighborhood.

I watched the couple from about 100 feet away, where I was getting ready to record a video interview. Once they had finished injecting, the two leaned back and relaxed, the woman resting against the man, and I turned my attention back to my interview. But after a while, I glanced back over and noticed the woman wasn’t looking so good. She was splayed out on top of the man with her neck tilted back, her mouth open. Her skin looked pale. The man was supporting her head, rubbing her breastbone, and checking her pulse.

The woman I was interviewing, Jasmine Johnson, is in recovery now, but was in active addiction on the streets of Kensington for six years. I looked to her face for cues, to see if my concern was warranted.

I had done enough reporting on overdoses that I thought I would know how to respond when I saw one. Plus, the city makes it sound simple: Billboards in SEPTA stations and along the highway advertise naloxone, the overdose-reversal drug, reading, ‘Saving a life can be this easy.’ With the state Physician General’s standing order, anyone can pick up naloxone (also known by the brand name, Narcan) at a local pharmacy without a prescription.

But suddenly, in the face of a possible emergency, it all seemed more complicated than that.

Jasmine went over to check on the woman, and offer her naloxone, which she carries in her purse. But the man angrily refused it. Jasmine tapped the woman lightly on the side of her face, to see if she would wake up. She didn’t, but still, the man insisted she was fine.

“She’s breathing!” he yelled, defensively. He told Jasmine he didn’t need Narcan, and that he already had some.

“Do not give her Narcan,” he mumbled. “She would be so mad.”

To understand why someone who uses drugs might not want Narcan during a suspected overdose, it’s important to understand how it works.

When someone is given Narcan, usually through a nasal spray, it bumps the heroin or other opiates off the opioid receptors in the brain. That blocks the effects of the drugs — both the euphoria of a high, and the slowed breathing that cuts off oxygen to the brain. That’s why Narcan saves lives.

But, in that process, it can also send someone into instant withdrawal. Many people who use drugs say withdrawal is like having the worst flu of your life, complete with cold sweats, shakes, and vomiting. Many people’s addictions are fueled by avoiding this feeling.

So, the man didn’t want anyone to give the woman Narcan for her sake — so she didn’t suffer withdrawal — and for his own, so she wouldn’t be mad at him.

While I knew all of this in theory, it just hadn’t registered to me until that moment that someone would risk death to avoid withdrawal.

‘It’s not easy’

As we wrapped up the interview, the woman still looked pale and unconscious. I didn’t know what to do, and Jasmine could tell.

“That’s all you can do, is ask and keep moving,” Jasmine said with a shrug.

But was that really all we could do?

“It’s not easy,” said Allison Herens, harm reduction coordinator at Philadelphia’s Public Health Department. She conducts regular trainings about naloxone and how to administer it, and recently led one for about two-dozen people at the South Philadelphia Library on Broad Street.

“There are lots of different kinds of emergencies that happen on the street in any moment and it can be hard to discern if it’s actually an emergency or not,” she told the group.

Herens stresses in her trainings that it’s important to make sure someone is actually overdosing before giving naloxone. She described a situation where someone might be nodding out, coming in and out of consciousness.

“The big thing to keep in mind with that person is, are they breathing? How does their color look? So they’ll start to get pale, grey – depending on the complexion, blue,” she explained.

Now, with the increased presence of fentanyl in the drug supply, Herens said the signs of an overdose are even more varied. Fentanyl often causes muscle spasms, or locked jaws in addition to the traditional signs she described.

She also confirmed that sending a drug user into withdrawal is a real concern, because if that person wakes up with those flu-like symptoms, he or she is going to try to get rid of them the fastest, cheapest way possible.

“If they wake up in full-blown withdrawal, they are not going to the hospital. They just are not,” Herens said. “They are going to go run as fast as they can to try to use again, and I know because I’ve seen it happen.”

If you suspect someone is overdosing, call 911

The first thing you should do if you suspect someone is overdosing, Herens says, is call 911.

Jeremiah Laster, a deputy chief at the Philadelphia fire department, whose EMS workers gave out Narcan over 5,000 times last year, agrees.

“Sometimes you have people that when you administer Narcan to them, they become combative because they’re upset because you sort of blew their high,” said Laster.

Because of this, he said there are some situations where it’s better for a civilian to stand back and wait for professionals to arrive.

“Certainly if you had someone that was like 6 foot 4, and 300 pounds, you’d want to be very careful how you wake that person up,” he advised. “You have to prepared to protect yourself.”

There are other reasons to call the police, too. Herens is careful to note that naloxone only works temporarily — it starts to wear off after about 30 minutes, and nearly dissipates after 90, depending on the person’s metabolism and the strength of the drugs. While the person’s body will likely have processed enough of the opiates by then that they are unlikely to stop breathing again, the much more powerful fentanyl makes that less of a guarantee.

Herens said fentanyl’s strength can also mean that multiple doses of Narcan are required to revive someone in the first place. And once you’ve given the nasal spray, she said it’s even better if you perform rescue breathing on the person, too. That’s because if they’ve already stopped breathing, any measure that could help resume oxygen flow faster will only help reduce risk for brain damage, or death.

For these reasons, she says it’s important to know from the start you have paramedics coming with back-up Narcan.

Ultimately, that day in McPherson Square, I did call 911.

Another woman nearby told the woman who was passed out that the police were on their way and that they had Narcan. And as soon as she heard that, the woman bolted straight upright. She and the man got up and left, but not without getting angry at the woman who told them the police were coming. There was a little pushing and shoving, and then, all three were gone.

Herens estimates she has given Narcan about seven or eight times — mostly during a recent spike in overdoses this summer, not long after the day I was in the park. She said she understands it can be hard to wrap your head around the fact that someone might get angry with you for trying to prevent them from dying of an overdose.

Still, Herens tries to keep it in perspective. At the end of the day, someone being irritated is a small price to pay.

“I always just try to remember that in this moment I am saving this person’s life,” she said. “They don’t have to like me.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.