Hear music made ‘using an entire building’ in a West Philly church

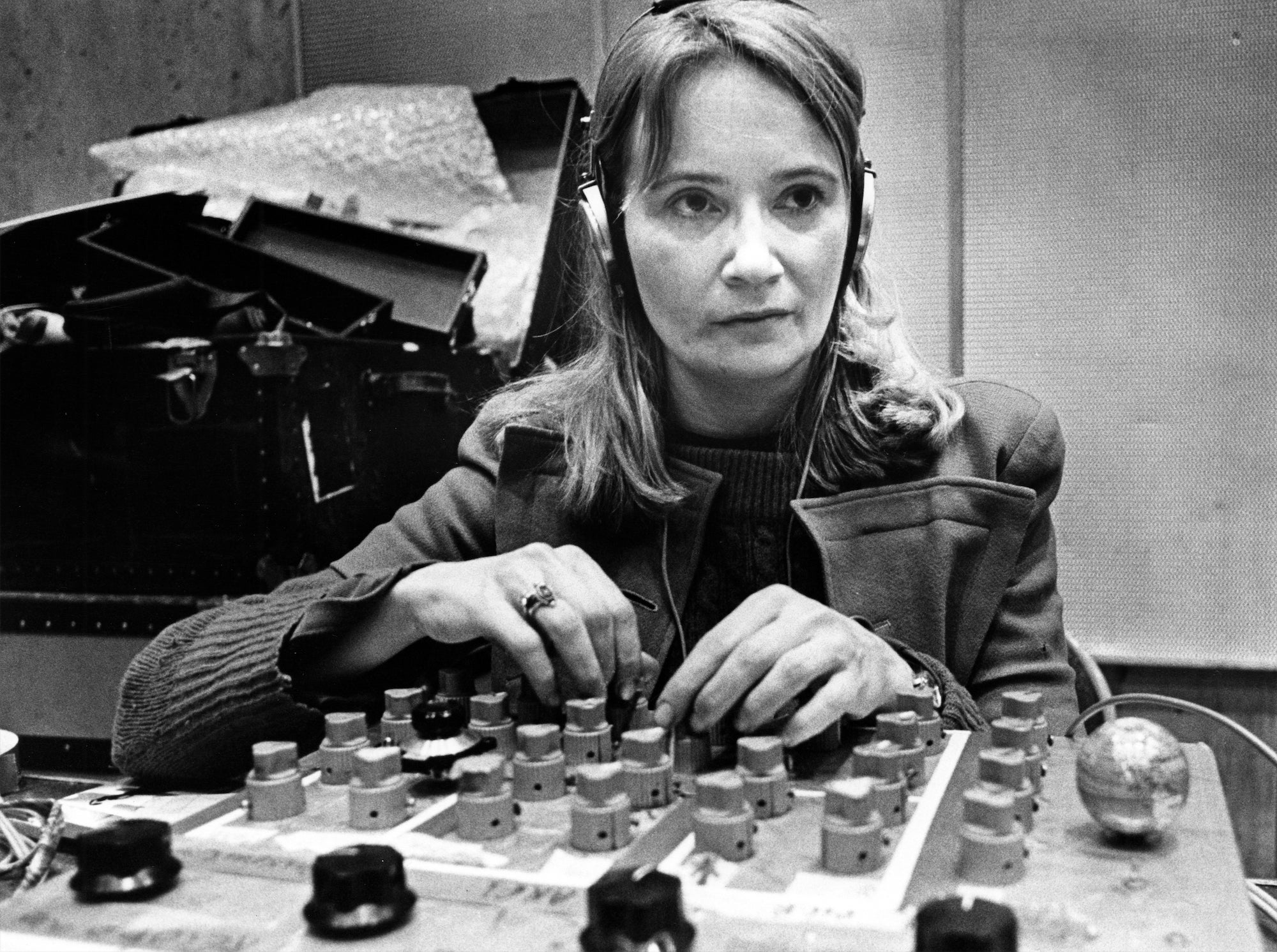

This weekend, a church in West Philadelphia will host performances of music composed by experimental sound artist Maryanne Amacher.

Bill Dietz is staging Maryanne Amacher's works inside the Holy Apostle and The Mediator Church in West Philadelphia this weekend. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

This weekend, a 150 year-old stone Gothic church in West Philadelphia will be used as a massive sound filter. Sonic works by artist Maryanne Amacher will be re-created at the Holy Apostles and the Mediator on 51st Street.

Amacher made experimental sound works that are something between music and installation art. She would, for example, set up 10 or more loudspeakers in a room, but instead of pointing them at the audience, they would be positioned toward structural elements of the building so that the sound would filter through the architecture.

Amacher was born near Erie, Pennsylvania, and would become a pioneer in experimental sound art. She would study music at the University of Pennsylvania, and under both Karlheinz Stockhausen — a champion of electronic Musique Concrete and manipulating pre-recorded sounds into aural artwork — and John Cage, a pioneer of composing by randomness and chance.

Bill Dietz, who worked with Amacher before she died in 2009 at age 71, says some of her pieces were not just about sound, but how the sound traveled to your ear.

“She’s really thinking about how does this sound when it’s not just playing in the space, but going through this wall,” said Dietz. “How does this transform my sound, how does it improve it?”

At the invitation of Bowerbird, an experimental music nonprofit based in Philadelphia, Dietz and the collective Supreme Connections spent a week rigging up Holy Apostles and The Mediator for a weekend of performances, which will include Amacher’s “Adjacencies” (for percussion and electronics) and “Petra” (for two pianos).

Dietz is careful to point out the performances will not be re-creations of Amacher’s pieces. She often worked on pieces that were site-specific, and uniquely reactive to that particular time and space.

Most of her later work in the 70s and 80s were made with Amacher’s own archive of recordings she made of seemingly random noses, that were mixed for a particular environment. There is no score that could be notated. They pieces cannot be replicated.

Instead, Dietz and his collaborators – most of whom knew Amacher personally — will create works that are informed by her ideas and her spirit.

“I struggle a little bit with the language because she was very persistent and insistent in not calling it a concert, nor an installation,” he said. “This kind of work where you’re using an entire building requires a different kind of format, a different kind of genre. “

One of Amacher’s first major works was a 1967 marathon radio broadcast in Buffalo, New York. “City Links” (which will not be part of this weekend’s program in Philadelphia) was created by setting up eight microphones in different parts of Buffalo, including the Pillsbury flour mill, the airport, and an open field.

Amacher connected each to a phone line that fed a control board in WBFO-FM, the radio station at the University at Buffalo. She mixed those sounds directly into a live broadcast of ambient and pre-recorded sounds in a continuous stream of noise, manipulated in real time. It lasted for for 28 continuous hours.

At the time, WBFO was programmed by Bill Siemering, who hesitated at first to give his radio station over to an artist for 28 hours. He ultimately came around to it.

“As a university station, I believed in experimentation, so I said, ‘Sure,’” said Siemering, who now lives in Wyndmoor, just outside Philadelphia. “It was a John Cage kind of thing.”

Siemering would later, in 1970, write a mission statement for what became National Public Radio, and helped develop the program “All Things Considered.” He said he had to push to get the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 – which created PBS television – to include radio.

“We had to make a fight for radio to be included in that,” he said. “They thought it was such an embarrassment, it would be a waste of money to invest in radio.”

In 1978 he became the station manager for WHYY, creating the daily show “Radio Times” and pushing “Fresh Air” into the national spotlight.

Amacher was an “intense person. Very dedicated to this work. Throughout her life she was a workaholic,” remembered Siemering, but those wild days of broadcasting urban noise for 28 hours on the radio are over. He admits it would be impossible to do that today. But Amacher’s experimental impulse informed his vision of what radio could become.

“This is what radio can do,” he said. “It’s a wonderful imaginative medium. It’s an intimate medium. It’s an immediate one.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.