Big bucks for child care: Families who don’t qualify for assistance say they need help

For parents, child care is the top expense after the rent or mortgage, a report said. The Philly median: $10,920/year for full-time day care for an infant.

Listen 5:09

Single parent Deshaun Sherrill and his son Zay’ion Ventura-Sherrill clean up the living room of their home in West Philadelphia. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

DeShaun Sherrill is a single dad who balances his 9-to-5 job as a records clerk at City Hall with the job of parenting his 6-year-old son, Zay’ion.

After a long day of work and school, Sherrill sat in their West Philadelphia row house and talked about making that balance work, keeping one eye on Zay’ion as the first-grader bounced back and forth across the living room gathering action figures, plastic insects, and trucks from a big box of toys.

“I just lost track because he’s picking up a car. What are you doing?” Sherrill asked his son.

“I’m making a whole city,” Zay’ion said.

This city counted Buzz Lightyear and Spiderman among its citizens.

Sherrill explained that Zay’ion is at school for most of the workday. But he still needs child care for him after school and during the summer. He makes just above the maximum to qualify for state subsidies that could help him pay for that care: about $34,000 for a family of two. But after paying rent and monthly bills, Sherrill said, he has virtually nothing left for child care.

“I have barely enough money still to eat,” Sherrill said. “What am I supposed to do here?”

Most working parents in Philadelphia can relate to that feeling, according to a recent report by the nonprofit Public Citizens for Children and Youth. It found that even two-child families making up to $75,000 are likely to barely break even financially after paying for basic necessities. Some at that income level, in fact, are likely to be taking on debt.

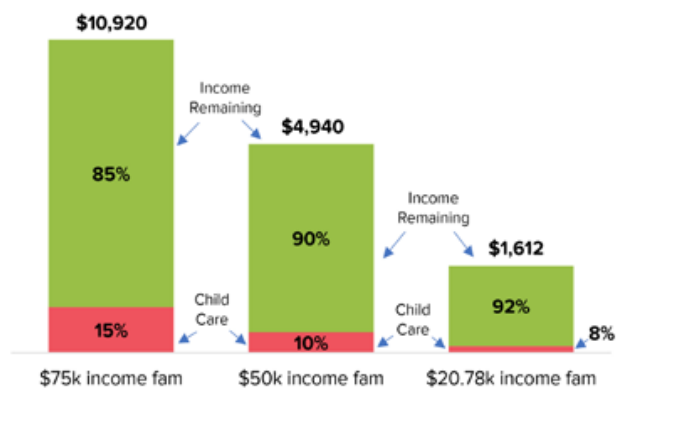

For families with young children, the report found, child care is the biggest expense after the rent or mortgage. It cited a median cost of $10,920 a year for full-time day care for an infant in Philadelphia. Providers with high-quality ratings can cost much more, and when a second child is added to the equation, a family’s total child care expense can easily exceed $20,000 annually.

Child Care Consumes Up To 15% of Families’ Budgets

The bill can be so big that some middle and low-income families in the city have to weigh whether a parent should continue working or stay home with the kids. A state subsidy program, Child Care Works, can help defray the cost for some working families, but it falls far short of serving all the children who would benefit from it. For middle-income families near the eligibility cutoff for public benefit programs, a promotion or a higher-paying job can mean that extra money is erased by the cost of child care.

Melissa Blatz, a 38-year-old mother of four in Fox Chase, used to teach kindergarten. But on a teacher’s salary, it wouldn’t have made sense to continue once she started having kids, she said.

“I would be working to pay for their child care,” Blatz said.

So she switched jobs and started working as the director of a child care center, Beautiful Beginnings, where she could bring her own children. All four attended the same infant care program there.

“So I would be working in my capacity and hear the cry of my child from the infant room,” she said. “But I had to have that extra level of trust that the caregivers would meet their need.”

Donna Cooper, executive director of Public Citizens for Children and Youth, said income caps for qualifying for state child care subsidies should be raised to help parents like both Blatz and Sherrill who make more than the caps allow.

“We need to make it possible for someone earning $75,000 to be able to qualify for some child care help,” Cooper said.

But first, she said, Pennsylvania’s underfunded Child Care Works program has to meet the demand from all the lower-income families who already qualify. There are more than 2,000 children statewide on a waiting list to receive the subsidies, according to the state Department of Human Services — 370 of them are in Philadelphia, where the average wait time is 68 days. Cooper said those numbers are just the tip of the iceberg, because the program isn’t widely advertised. There would be thousands more signing up if it were better known, she said.

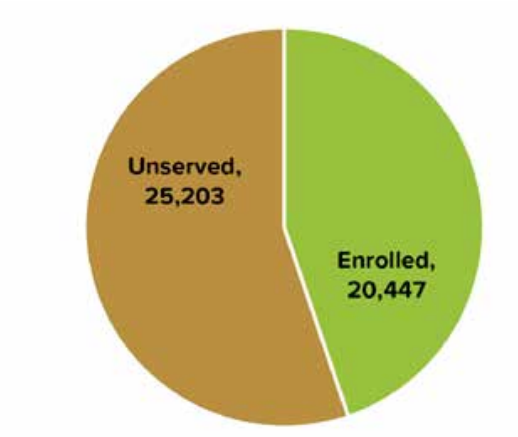

All told, only 45% of Philadelphia children who are eligible for Child Care Works are enrolled in the subsidy program, according to the Pennsylvania Partnerships for Children, whose data is cited in the Public Citizens for Children and Youth report. Serving them all would require a lot more funding, most of which comes from the U.S. government. The federal budget for child care assistance has seen big increases in recent years, and Pennsylvania received an additional $56 million in federal money for the current fiscal year.

“But we did lose state funding that we could have used to fill this waiting list problem,” said Diane Barber, executive director of the Pennsylvania Child Care Association.

Barber said the $36 million the state cut from its child care budget would have been enough to clear the waiting list and then some.

Still, national child care advocates say billions more federal dollars are needed to ensure that families nationwide can access quality, affordable child care. They called for a $5 billion increase in funding this year, but the new federal budget signed by President Donald Trump in December increased funding by just $550 million.

So, working parents look for stopgaps.

Majority of Eligible Children Don’t Receive Subsidized Child Care

Sherrill’s son goes to a free after-school program at Martha Washington School where he can pick him up after work. The school also offers an affordable daytime program where Sherrill sent Zay’ion last summer. But it let out in the middle of the afternoon, which made for a hectic routine.

“I would take my lunch break at like 3. I would run home, pick him up, and go right back to work. Try and grab something on the way, like snacks and stuff. Maybe a quick pizza from like Wawa or 7-Eleven, something like that. And he would sit at work for me for like an hour and a half.”

Sherrill has a side business as a visual artist, drawing commissioned artwork and designing graphics for hoodies. He hopes to eventually make his business full time, which he said would give him more flexibility to look after Zay’ion.

But as for what he’ll do about child care this summer, Sherrill said he’ll cross that bridge when he gets there.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.